Bothy dreams

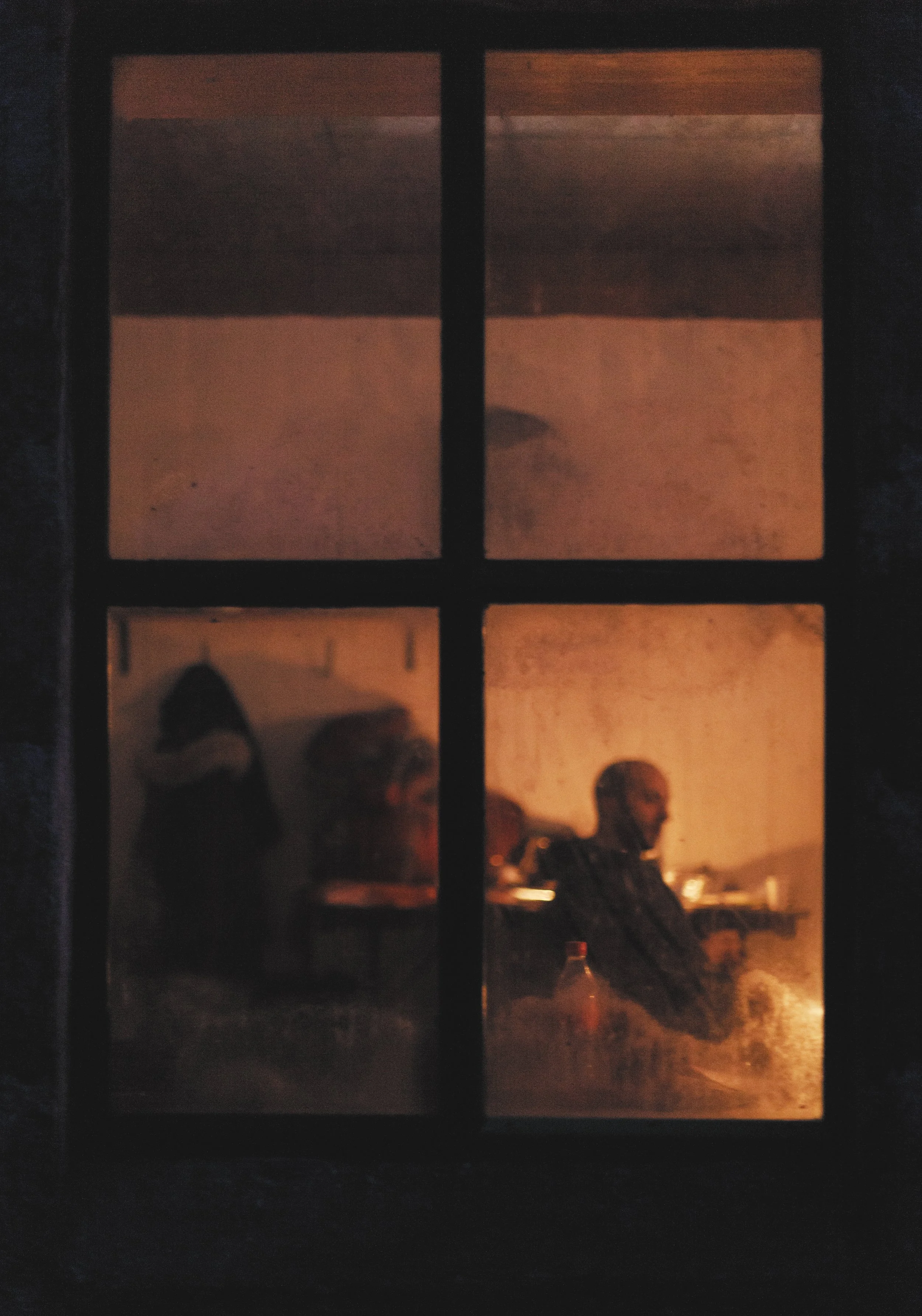

Sanctuary awaits after the long walk to Glenpean bothy

A crackling fire, the company of strangers and, outside, miles of unspoiled wilderness. Alba Chiara Di Bari falls for the restorative pleasures of bothy life — and picks five in Scotland for sanctuary and solitude. Original photography by Emanuele Centi

We parked the car at the entrance of Rannoch Moor as the first rays of sunlight touched the snowy peaks of Glencoe. The walk towards Lochan na h-Achlaise across the icy bog woke us up more abruptly than the alarm at three o’clock that morning. Crunching under our feet, the frozen branches of heather soon became a rhythm to which our warm breaths danced shapelessly, fighting the cold air.

On the banks of the loch the water rested motionless, caught under a blanket of thin ice. I gazed at the shoulders of Glencoe, glorious in the early light, turning from white to silver, then indigo, pink and finally gold. We had been blessed by an improbable clear sunrise, and I stood breathless, bathing in its colours, overwhelmed by the beauty of nature and grateful for that moment and sight. We were on our way to spend a night at A’Chuil Bothy, and the journey felt already like a destination.

The reason for our endeavour was a book, or better a philosophy implied between the lines of that book: The Scottish Bothy Bible, by Geoff Allan. The tale of Bernard Heath and his friends and how they founded the Mountain Bothy Association in 1965 to allow fellow walkers to experience Scotland at its wildest is both inspiring and humbling. We felt moved by that desire of the unknown, the attraction for unconquered, untamed lands that stirred explorers for centuries.

We were also tired of being distracted by sounds and screens and scarred by the recent lockdown. So, like countless others, we turned to the outdoors, to the wilderness, in search of better ways of feeling small, and becoming part of something bigger.

Putting the kettle on at Invermaillie bothy

Of the trip to A’Chuil, and of the many other bothy weekends that followed, I remember the endless walks across valleys and rivers, forests, and moors. Close encounters with grazing deer barely bothered by our presence, numerous songs to annoy my hiking companions, and the many moments when we realised that we should have already been at the refuge, but it was still not in sight.

With no signposting, no GPS and no phone reception, reaching a bothy is a constant battle between mankind and nature: a missed turn, a flooded path, or a fallen tree can hinder the expedition at any moment. But then there’s the joy following hours of walking or cycling of glimpsing a chimney spiking across the landscape, or a stone wall among the bushes, or the reflection of the low sun from a window in the woods.

‘I remember the endless walks across valleys and rivers, forests, and moors. Close encounters with grazing deer barely bothered by our presence’

We learned with experience that it is good manners to knock before opening the door of a bothy, and that the earthy smell of extinguished embers, moss, and dust that enwraps you once arrived there marks only a stage, not the final stretch. A ritual has to be religiously followed to transform the cold shelter into a temporary home, from an assessment of the sleeping conditions to the exploration of surroundings to find a water source and outdoor loo – always rigorously away from each other.

We make sure we have enough fuel for the night, light the fire, hang up our wet socks and jackets, put on the kettle, start preparing dinner, and finally toast our good fortune with a decent dram. With a sense of satisfaction, we settle for the night, among a card game, a song contest, and a quarrel over what to write as our entry in the bothy visitors book.

Waiting for the rain to stop at A’Chuil bothy

Sometimes, we are joined by other campers and those nights are the ones that I keep dearest in my mind. Like the time at Glen Duror in the middle of winter, when we arrived at the bothy despondent and soaked with rain, after having to trace our steps back twice to find it. A gentle hillwalker had already started a fire, and he offered us warming cups of tea and reassured us that plenty wood had already been cut. We thanked him and offered to share our food. An hour later a solitary hillwalker arrived, and then a couple from France appear seeking refuge from the rain. Sleeping bags are pulled out and room on the wooden platform where we’ll sleep divided up to give everyone a little space away from the floor.

‘Inside the bothy, the damp smell of smoke, the trembling flames of candles, the comfort of some companions, and a scotch whisky was all we needed’

As the night unfolds, conversations between strangers accompany the pleasing crackle of the fire. Outside the storm is building up, branches bashing against each other, heavy rainfall battering the tile roof. We wonder about the people who used to live here in the past, with no running water, no toilets, no electricity, miles and miles away from any human dwelling. We thank these bothies for offering us shelter and plan the goodies to leave behind the day after as a courtesy to the next visitors – mainly candles and toilet paper.

Glenpean bothy’s spectacular location at the foot of Carn More, Spean Bridge

Inevitably, someone pulls out a bottle of whisky, someone else chocolate and biscuits, and while we share these treats, we toast the simple things. A distilled cereal forgotten in a cask, a centuries-old piece of dirt burnt for warmth, four stone walls in the middle of nowhere.

The world could have ended in that moment, but inside the bothy, the damp smell of smoke, the trembling flames of candles, the comfort of some companions, and a scotch whisky was all we needed. We travel far away to put things in perspective and sometimes we stumble upon their real value. We often look for peace away from society, just to find out again and again that human connections are the only fires that truly hearten us.

For more information on where to stay and how to bothy hop safely and responsibly visit https://www.mountainbothies.org.uk

Five of my favourite Scottish bothies

Walking in the wild Highlands you’re never far from a welcoming bothy

In The Scottish Bothy Bible, Geoff Allan lists almost a hundred bothies scattered across Scotland, 81 of them under the stewardship of the Mountain Bothy Association, and thus free to use for hillwalkers, campers, and cyclists. Here are some of my favourites…

1. For outdoors sport: Uags, Applecross

Ideal for lunch stop or summer staying, Uags is conveniently located close to the Bealach na Ba mountain pass, famous among cyclists, and to favourite kayaking spots of the rugged north coast of Scotland.

2. For unforgettable scenery: Glencoul, North Highlands

Those strong enough to endure a three-hour walk to reach this tucked away beachside bothy will be rewarded with unique views over the fjord to the North Sea, a stone thrown away from UK’s highest waterfall, Eas a’Chual Aluinn.

Contemplation in front of the fire at A’Chuil bothy

3. For a glimpse of wildlife: Guirdil, Isle of Rum

A pearl on the northwest coast of the National Nature Reserve of Rum, Guirdil is the perfect location to spot dolphins, porpoises, and numberless of seabirds, while sipping a hot tea cozily wrapped up near the fireplace.

4. For solitude: Meanach, Corrour

In one of the most remote locations at the centre of the Highlands, Meanach compensate the challenging four-hour hike across the vast moorland with a view on imposing Munros and a peaceful atmosphere away from mundane worries.

5. For a romantic weekend away: Peanmeanach, Ardnish Peninsula

Standing solitary on a high beach overlooking the astonishing Ardnamurchan and Eigg, Peanmeanach Bothy is a picturesque dwelling in a location rich of history and stunning geology.

Alba Chiara Di Bari is a storyteller & tour guide with a passion for whisky, currently working for Johnnie Walker.